ANTICLIMACTIC

…forgoing a good ending…

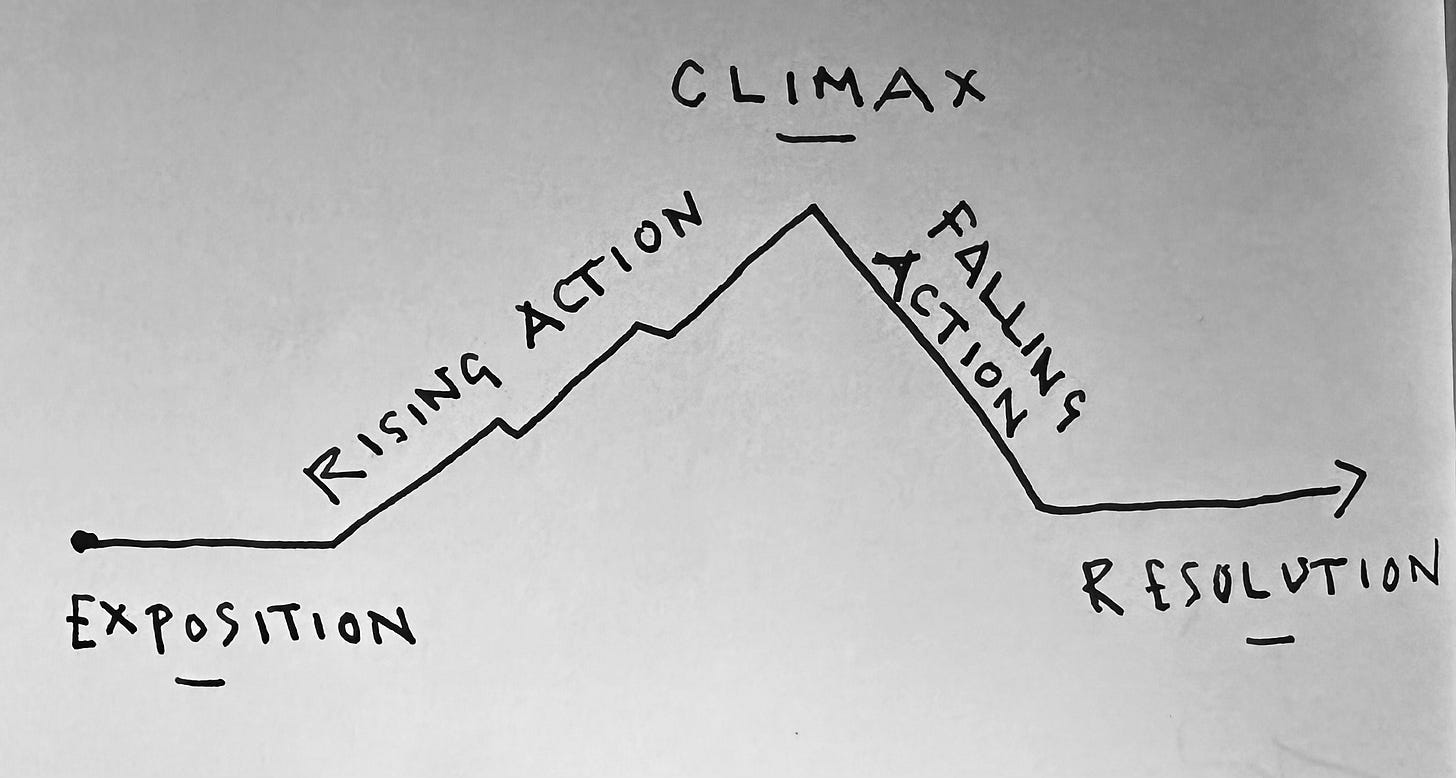

…so, there exists a common universal template for narrative structure—see Antigone—just as there is a similar template for a sonata (listen to Beethoven’s or Schubert’s piano sonatas) or for the composition of a landscape painting (think of Patinir’s pioneering panoramas or a Samuel Palmer artwork). Even Dickens’s serialized works led the reader to an ending. Whether a story or artwork conforms to or subverts this template, it typically moves through exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and finally to resolution.

There is comfort in this model. We have come to believe it mirrors the arc of a human life: birth as exposition, death as resolution. This familiarity shapes our expectations. We expect the martyr to die, the chord progression to resolve, the composition to counterbalance. We even expect reality to behave this way: the marriage to survive its challenges; the accident to lead to a hospital stay, then a return home; the disruption to give way to restoration.

But increasingly, our stories are resisting ending.

Streaming series—our modern fireside tales—have proliferated beyond anything imagined in the era of Upstairs, Downstairs or Dallas. Yet despite this explosion, many of these series are not renewed. Writers are forced to construct story arcs that might stretch across seasons that never come to be. And so the stories we encounter often conclude at the climax or in the throes of falling action, denying us resolution, if not renewed, or end up being postponed or in production for years.

We love good endings. We crave them. Life rarely offers operatic finales—nothing as decisive as Tosca or the Don Giovanni. More often the “resolution” is now a flat line, a return to status quo without eventual catharsis. Yet in our fictional lives—novels, films, dreams—we expect closure: happy or tragic, but something that rounds off the experience and grants it meaning and even purpose.

Streaming, however, introduces a new constant variable: the business model. A story is now held hostage to platform metrics, budget calculations, and renewal decisions. As a result, our collective narrative life is increasingly lived in suspension—paused mid-sentence, trapped in a perpetual ellipsis.

Consider how many of our communal streaming stories—Pachinko, Downton Abbey, Le Bureau, La Casa de Papel—have become global myths. And yet even these sagas have taught us to expect disruption, hiatus, unresolved arcs. We live in anticipation, rarely in completion. There is always the possible promise of a sequel that may or may not arrive.

Perhaps this is the zeitgeist. Beta-tested software is never finished. Legal processes increasingly drag on for years with appeal after appeal. Democracies stall in legislative limbo. If earlier eras prized the “good ending,” we now seem resigned to an endless deferral. Delayed gratification as a lifestyle.

Years ago, I became friends with Walter Mischel, the psychologist behind the famous Marshmallow Test. His research showed that the capacity to tolerate delayed gratification was beneficial. But in his experiments, gratification was only delayed—never denied. What happens to the psyche when resolution is not merely postponed but potentially abandoned altogether?

Artists, of course, have long played with incompletion. Tristram Shandy never escapes its own exposition. John Cage’s 4’33”, in some ways, never really begins nor ends. Many abstract paintings, such as Jackson Pollack’s, read as perpetually in-process. In art, the “unfinished” can be a powerful, destabilizing form.

But the difference now is density and ubiquity. The unfinished has become a daily narrative diet for a global audience. Instead of occasional formal play, we experience constant structural deprivation. And that produces—quietly but pervasively—a sense of collective unfulfillment.

In some ways, this might be healthy: a reminder that we, like the cosmos, exist in flux; a nudge toward embracing the Heraclitean condition of ceaseless change. Yet I suspect that one reason humans told stories in the first place was to erect a bulwark against that very flux. Narratives gave shape, certainty, solace. They resolved what life could not. We may not be able to hunt and find our meal but the story at night could offer some satiety.

And when that resolution becomes scarce—when endings recede indefinitely—it is unsurprising that anxiety increases. Certainty, even artificial certainty, can be an effective psychological balm.

So perhaps this is simply the sign of our times. Perhaps living without endings is the new normal. But perhaps—notwithstanding the chaos that swirls around us—we would be better off seeking out good endings, crafting them intentionally for ourselves, allowing us the closure our stories once promised.

Keep well, and may you find a good resolutions somewhere…

Love this piece. And the marshmallow wait did presume promise would be kept. Starting to doubt lots of presumed outcomes now.

So true.